The Neurological Foundation x Capsule

For the thousands of New Zealanders with neurological conditions like Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s disease, the genetic component to these diagnoses can feel like an inheritance nobody asked for. But thanks to the work of the Neurological Foundation Human Brain Bank, there is now world-leading research helping improve the outcomes for those with these conditions – and their children. Emma Clifton talks to Micheal Hanly, who is the third generation of his family to have Huntington’s Disease, and Sir Richard Faull, a man whose hope, enthusiasm and genius has helped change the world.

March is Brain Awareness Month and here at Capsule – along with the Neurological Foundation – we’ll be bringing you a selection of stories about how you can actively work to help prevent any premature powering down, plus what signs to look out for that things are amiss. Today we’re bringing you the story of a Kiwi pioneer in neuroscience, a trailblazer who has established NZ’s brain bank to further neurological research and who has gone on to inspire multiple generations of scientists and clinicians to look at how they can contribute to a brighter future through brain research.

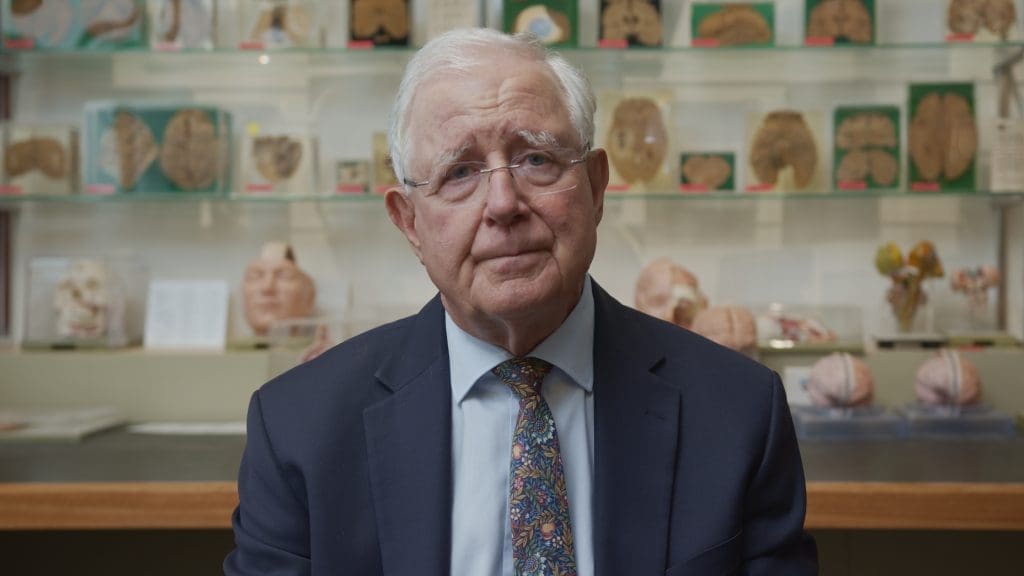

When it comes to the work of Sir Richard Faull, the Director for the Centre for Brain Research and Director of the Neurological Foundation Human Brain Bank at the University of Auckland, it’s the connection to the whānau he serves through the brain bank that has been the secret behind his success in the field of Huntington’s Disease. Huntington’s, a rare and degenerative neurological condition, becomes an uninvited part of a family’s inheritance, due to its strong genetic component – if your parent has the Huntington’s gene, there is a 50% chance that you do as well. This then becomes a generational cross to bear but, as Richard says, it is the power of the whānau involved that is the reason the science is so advanced. “That’s the wonderful thing about Huntington’s research – it’s a big family and, more than any other disease, people collaborate and work together for the common end.”

Over the past 40 years, Richard and his research team have become world leaders in Huntington’s research and even managed to help identify the Huntington’s gene in the brain, with an international clinic trial currently underway with 909 subjects around the world undergoing a treatment that may turn down the gene and its effects.

But it’s one thing to read about such a study, it’s another thing entirely to know that it may help you and your family. For Micheal Hanly, 34, this breakthrough provides light at the end of the tunnel that has long been missing for families with Huntington’s. Micheal’s grandfather, the famous New Zealand painter Pat Hanly, died of Huntington’s in 2004. In early 2017, Mike’s father was diagnosed with Huntington’s and in late 2017, so was Mike. Mike has a gorgeous seven-month old son, Finn, who sits bouncing on Mike’s lap during this Zoom meeting between Mike, Richard and Capsule. This type of inheritance is happening to families around the world, as it is to families who also have genetic conditions like Alzheimer’s or motor neurone disease. Having a resource like the Neurological Foundation is invaluable for people like Mike who are looking for more information, without falling down internet wormholes.

“I first made contact with the Neurological Foundation when my dad was going to get tested – my auntie had already done hers a long time ago and she knew she had it. So, it was when my immediate family were starting to come to the awareness that my dad and his kids had the potential to have this disease.” Mike reached out to Dr Malvindar Singh-Bains, an expert on neurodegeneration who is part of Richard’s research team. It was brilliant, Mike says, to have a resource he could trust. “As soon as you jump onto the internet, it’s the worst possible outcome. So, the Neurological Foundation puts a much more human face on things and it feels like a much safer space.”

The Neurological Foundation Brain Bank started on a very ad-hoc, very Kiwi basis. Richard was working in Huntington’s research at the time when a colleague asked him to look at a donated brain from a family who had been told that their (deceased) loved one had Huntington’s. At that stage, a clinical diagnosis was all that was available but it wasn’t a conclusive diagnosis and due to the generational impacts of the disease, they wanted to know for sure.

“I naively said ‘Oh, I’d love to,’” Richard says of his first donated brain. “So [my colleague] would come along and bring another brain from a family in the South Island, or Nelson, or Hokitika, and we would sit down and treat it in the most respectful way, taking sections of it and running tests. Then we could say yes or no, definitively, to the families. The families then said ‘keep the brain and do research on it.’ And that changed my life.”

The Neurological Foundation Brain Bank is now the key to the success of the research team and an important part of the international collaborative research network as well. To have a family entrust you with their loved one’s brain is an act of such total generosity, Sir Richard says. “The families are giving us a gift. You can’t give a gift that is more valuable than that – the brain of your mum or dad. You can’t put a value on it; it’s what they are and to entrust it to us… I always say, ‘We’re the custodians of the brain, we don’t own it. It will always belong to the family or the whānau.”

When Richard and his colleagues first started doing research on the donated brains, they found that the pattern of cell death was not only different from what was in the text books, the patterns also varied hugely from each other. Each person had died with Huntington’s, but how the disease had affected their brains was completely individual. “It took me 10 years to realise how varied they all were; we collected them over the years, got the results, and went and talked to the families. Going to the family meetings was the most empowering part because families hung on every word you said and you suddenly realised, you were there for them. That’s what I love – it keeps you humble, and the more you find out, the more they get excited.”

But as fascinating as the brain-research results were, they didn’t paint the full picture of why each brain was so different. So, the research team decided to send psychologists out to talk to each family and create a full, detailed family history of the individual, to sit alongside their brain, as it were. And those stories, Richard says, were the secret to the success of the scientific findings. “Because the variations of the symptoms we found in the brain were reflected in the variations of the cell death, that means we could relate patterns of cell death in the different parts of the brain to different patterns of symptoms. Then we could see how and why the brain was reflected in the changes, and the clinical history would empower us. It was exciting and it was original – we were the first people in the world to do it. But we were only able to do it because the families said ‘Keep the brain, do the research and see if you can help our children.’”

The importance of lifestyle choices on brain health is well known, but they are particularly crucial for people who carry the gene for degenerative neurological conditions like Huntington’s. After Mike’s diagnosis, he was given great advice from Malvindar, and set about making big changes in his life to help protect his brain health for as long as possible.

“I left a high-stress job and changed my diet, so that it was more of a Mediterranean diet, because that’s what Malvindar advised,” Mike says. “I’m now careful with my life and the people I choose to spend time with because it’s important to avoid extreme stress. I’m careful with my drinking and I do lots of physical activity, as well as meditation. Just being far, far more careful with my choices – probably just following all the things we should all be doing anyway.”

Having a sense of agency is important but the most crucial aspect for everyone involved in the fight against Huntington’s is to have a sense of hope. The research being done by the Neurological Foundation is providing that hope for generations of families affected by this disease. “It’s pretty extraordinary,” Mike says. “I follow all of the Huntington’s news sources and a lot of the time, it’s not that great. But when it does sound like something good is happening, I can cross-reference it by getting in touch with Malvindar and seeing what she thinks. I think because it sort of dovetails with talking to my dad and my auntie, who are now both experiencing symptoms. So that’s very anxiety inducing but then, at the same time, you can see that things are happening alongside. It doesn’t feel like it’s a lost cause – it always feels like there’s some light at the end of the tunnel.” The research that Richard mentioned – with the ability to turn down the gene – was released just after Mike got his test result. “I was feeling pretty rough around the edges and that was very, very, very exciting to read about.”

“We now have enormous hope that we’re going to have a genetic treatment for Huntington’s disease in the next few years,” Richard says. “We can then give that enormous hope to people like Mike and his whānau, so they can then have that hope about what’s coming in the next five to 10 years. And this is all because of the enormous international research collaboration that we’ve been able to do on the human brain. The Neurological Foundation have helped us with the Human Brain Bank for decades and no other brain bank in the world has this level of contact with the families. It’s the families who have made this all happen – they’re the reason this disease will no longer be incurable. And for people like Micheal and his son, that’s worth a million dollars.”

About The Human Brain Bank

The Neurological Foundation has supported the Human Brain Bank since 1994, with $3.3 million having been provided over that time.

In the last five years the Neurological Foundation has committed over $310,000 to Huntington’s research, ranging from basic science to clinical studies. Last year the Foundation awarded a two-year project grant to Associate Professor Deborah Young, Associate Director of the Centre for Brain Research and Director of the NeuroDiscovery Behavioural Unit at the University of Auckland, which is co-funded by the Auckland Medical Research Foundation. Deborah and her team have developed a switch for use in gene therapy that can turn on and direct the therapy to sick neurons only at the time of need. In this project, they will test the switch in a model of Huntington’s disease.

Professor Bronwen Connor, head of the Neural Reprogramming and Repair Lab at the Centre for Brain Research, had two Neurological Foundation PhD students who developed the technology to grow brain cells from the skin tissue of patients with Huntington’s. In 2019 the Foundation awarded Bronwen a small project grant to use this technology to investigate whether lithium can prevent brain cells from dying.

As swallowing impairments (dysphagia) are the main cause of death in Huntington’s, the Foundation awarded $12,000 to The University of Canterbury Rose Centre to trial a skill-based swallowing therapy in patients with Huntington’s. Although this was a preliminary study with a small number of patients, the results indicate this is a feasible treatment for patients across different stages of the disease and will be used to inform further trials.

Thulani Palpagama is nearing the end of her PhD at the Centre for Brain Research, funded by the Neurological Foundation. She is looking at how different symptoms in Huntington’s disease are related to inflammation and changes in the brain cells. Thulani is hoping to find potential targets for treatment. The Foundation has also supported her to present her research at international conferences, which is an important part of research development.

Research is the only hope for a better future.

This year also marks the Neurological Foundation’s 50th anniversary. Over the last 50 years they have funded over $50 million in research and education to give hope for a better future to the 1 in 5 Kiwis affected by a neurological condition. This has only been possible through donations from everyday people like you.

You can make a difference to someone’s future today by donating to the advancement of neurological research.

A lot has changed in the last 50 years, but one thing remains, the need to know more about the human brain. It is only through research that we can accomplish this, and we need your help. So why not help make a difference and show your support by donating at brains.org.nz