Award-winning writer Sarah Jane Barnett has just released a part memoir, part feminist manifesto called Notes on Womanhood, which covers a whole host of topics. In part one of Capsule’s two-part conversation with the author, we look at why middle age should be a celebrated not stigmatised part of life, rejecting beauty norms, embracing the messy bits of life and more.

You know that kind of book you don’t know you need until you read it – then you want to read it again and lend it to all your friends? Notes on Womanhood (Otago University Press) by award-winning writer Sarah Jane Barnett is one of those books. It’s part memoir, part coming-of-middle-age story, and part feminist manifesto – touching on everything from the male gaze, being called chunky and stopping beauty treatments, through to having a hysterectomy and having a father coming out as transgender.

The author, who has a PhD in poetry, has published two books of poetry, and has had poems, essays, interviews and reviews published in journals and magazines. Sarah, who also teaches creative writing at Massey University and works as an editor of books, lives in Te Whanganui-a-Tara (Wellington) with son Sam, 11, and her husband Jim, who works in IT.

Part One:

(Navigating the male gaze, weight talk, rejecting beauty treatments, guys being dicks, ‘messiness’, sexist healthcare, becoming invisible)

Why write this book?

I had to carve out time to write this book, in between trying to work as a writer, editor, teacher and parent. I actually didn’t know if it would become a book at the end! In a way that was good, because I wrote it as though no one would read it. I didn’t go, “Oh, I’m going to write a book on womanhood”. But I’m at the start of what would be considered middle age, so the book is about that ‘becoming’.

What’s your hope for the book?

My goal is to share my story and the work of the writers, creators, YouTubers and other people I’ve encountered along the way. And in a small way, to help women to embrace themselves and to help bring women closer together – and through that to hopefully empower them.

Your book feels partly like a feminist manifesto. Is it?

Well, I’m a trans-inclusive feminist [considering trans women to be women] and an intersectional feminist [understanding how women’s overlapping identities and backgrounds impact their experiences of oppression]. So, the book reflects that and is feminist in its goals.

“I think that trying to fit into that notion of ideal womanhood involves self-abuse.”

You write that “over the years I have tried to erase the history of my own ageing. I have polished, exfoliated, promoted cell growth, infused my own skin with ultrasonic energy, exposed my face to wavelengths of light, dyed, contoured, reduced, refined, reshaped, slimmed, firmed, hydrated, sculpted, smoothed, controlled and targeted myself with a refreshing cream”. Have you given up these things?

I still like nice skincare products, but I’ve stopped most of the other things. I’ve stopped dyeing my hair. I’ve stopped fake tanning my legs, which I did every few days for about 20 years.

You also write that having been in thrall to ‘society’s ideal of womanhood’ felt like you were defending yourself against an ‘abuser’?

I think that trying to fit into that notion of ideal womanhood involves self-abuse – whether that’s getting beauty treatments that scrape off your skin, food restriction, over-exercising, or constantly telling yourself you’re not good enough. Imagine if another person was starving you, overworking your body, and saying mean things about you. That would be an abusive relationship.

How do you manage to get out of that relationship, so to speak?

I try to look critically at my beliefs, assumptions and behaviours, and at the gap between my behaviours and my values. I notice contradictions. I still occasionally look in the mirror and think, ‘oh, maybe I should go get some skin needling or a laser peel’, then I catch myself and think, ‘no, that doesn’t align with my values’.

You mention you’re attached to your long hair.

While I’ve been able to drop lots of gendered behaviours, some are just so ingrained in my psychology and sense of safety, like my long hair. I don’t want to put myself across as some ‘fixed person’, as I’m such a work in progress. If you said “Sarah, you have to get a pixie cut,” I’d have a panic attack. That’s why I won’t judge someone if they’re trying to lose weight or fasting, or doing other things to feel safe or good enough.

I feel like in society, we get praised for weight loss.

Absolutely. It places our value on the size of our body. It’s incredibly dangerous, because if you gain weight, are you less valuable? Less praiseworthy? I was probably in my early 30s when I was like ‘no more dieting’. I read Geneen Roth’s book When Food Is Love, I started intuitive eating, and found the body-positivity movement. Now I don’t restrict my food.

“In Western society there’s only really a story of decline for middle-aged women and no positive stories about what we’re ‘becoming’.”

You don’t deny yourself treats?

I just call it all food.

I got rid of my too-small clothes recently, but I’m still trying to be okay with the size I am.

I think that’s where the work is. I feel scared because I’ve always been a size 10, and now I’m a size 12. I’ve always been this slim runner and now I’m a ‘slim-ish’ runner. And in 10 years, who knows? But I know that trying to control my weight just creates pain. By accepting it, I feel I’ve come quite a long way, but it’s still hard.

You wrote that, when you were younger, some guys you were involved with said things like ‘you’re chunky’, or ‘I don’t usually have sex with fat girls’. Did you realise at the time how awful that was?

I didn’t, because I was young. I felt a real pressure to look a certain way and I believed that’s what I owed these boys. I felt like the fault was on my part, not theirs.

There’s that insidiousness of the ‘male gaze,’ as in a way of portraying and looking at women that empowers men while sexualising and diminishing women. Do you think it’s so normalised we don’t really think twice about it?

Yes, definitely – it’s internalised by all genders. It causes dysfunction for everyone.

Did those comments from guys make you feel body dysmorphic at all?

No. I’ve always been athletic and a bit chunky in that I’m broad shouldered. And at university, I put on weight as people do. My weight went up and down. Looking back at photos, I just look like an average-sized girl. And even if I had been fat, which is totally okay, it’s not appropriate for people to rate or judge my body. It comes from a culture of fat phobia. Imagine a society where ‘fat’ was just a descriptor like ‘tall’, with no judgement at all.

Tell me about what happened when you found out you needed a hysterectomy and a doctor said it wasn’t going to ‘make you less of a woman’. WTF! Did you think he knew he was being rude and insensitive?

He had no idea. A friend who read that part of the book messaged me and said, ‘I know who that doctor is’ because his wife had seen the doctor as well. That was just his bedside manner which is appalling, especially as I was already feeling vulnerable.

“That’s the other invisibility: being squashed into this box of middle-aged woman.”

You write that the ageing process has made you feel invisible and irrelevant. To men?

I think to everyone. For me, there are two types of invisibility. There’s the going-up-to-a-bar-trying-to-get-a-drink invisibility where younger people will probably get served first because the bartender will usually be younger and gravitate towards people of their own age. So, there’s that sort of invisibility.

And you write about the young guy in the shoe store looking surprised and saying ‘Oh, my mum runs too’. OMG!

Yes! That’s the other invisibility: being squashed into this box of middle-aged woman. He must have been 18 or 19, and he couldn’t see me as a runner. It happened another time with a female staff member when I was buying trail shoes. ‘I said, “I’m going to do this race,” and she’s like ‘Are you really?’ with confusion.

Do you think that, as women, we hide – sometimes even from ourselves – our fear of entering middle age?

Yes. In Western society there’s only really a story of decline for middle-aged women and no positive stories about what we’re ‘becoming’. What if, instead, we had a story of ‘wow, I’ve learned so much from longevity, and my wisdom has grown, and look how strong my relationships are’? There could be a forward focus – like when you’re an adolescent and excited to move into the next stage of life. When we approach middle age, we tend to just look back.

Did it feel exposing to write about personal things?

There are very personal moments, including moments of shame, in the book. But while I experienced them, they are things that have now ‘gone’. So it’s exposing in a sense, but it felt very true to myself.

When you say shame, do you mean around buying into the idea that we have to look a certain way?

Around beauty ideals definitely. But also around not quite knowing where I was going in midlife. There is that uncertainty, which isn’t shame, but is more like, ‘oh, in my 40s, I should be more together than this’. It’s my ‘messiness’. I love that Maggie Nelson quote: ‘Shit stays messy’. I think often women are expected to not show that mess. To put on a façade of everything being okay. It’s about letting go of that need to be ‘neat’, which I find difficult still. But I let myself be messy more, and let my mess show.

You write about a lack of rituals for some things. Wouldn’t it be cool if there were celebratory rituals for menopause, first periods, pregnancy, divorces, and people who decide not to get married or marry themselves?

Yes! Faith communities have had thousands of years of developing rituals, but people who are secular don’t really have those kinds of rituals. In Western society our rituals are quite consumerist, and circle around the giving and receiving gifts. It’s all very external and celebratory, which is fine, but it rarely creates a space for contemplation and transformation. But we can create our own rituals.

Would you like there to be a ritual around entering middle age or would you prefer that it’s not even ‘a thing’, because in some cultures or communities the idea of ‘middle age’ doesn’t even exist?

I quite like both ideas. They don’t negate each other. I’d like to see less emphasis around midlife as this ‘decline’ and less focus on the physical changes that happen, when really it’s about identity and our next stage of ‘becoming’.

Do you hope this book might spark conversations between people, whether that’s between female friends or between a woman and her partner?

Definitely. A friend told me her husband had read my book, and it had sparked conversations between them. I’ve had people who aren’t women message me and say, “This has helped me understand more about gender, womanhood and these issues.” I’m glad and grateful that people are reading and responding so well.

Click here to read part two, where Sarah talks about the difficulty of motherhood on her mental health, having a parent come out as transgender while staying in a happy, long-term marriage, and the value of ‘doing nothing’.

Notes on Womanhood (Otago University Press) by Sarah Jane Barnett is available to buy now

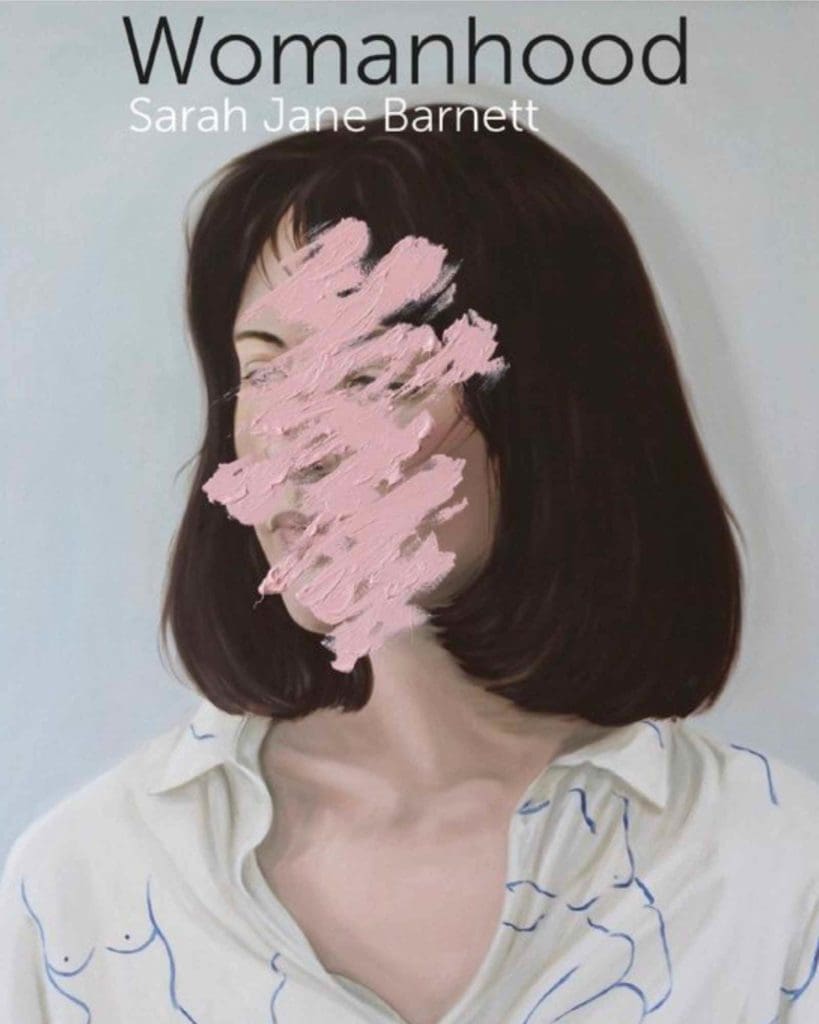

You can find Sarah’s work at: sarahjanebarnett.net Notes on Womanhood cover image by Henrietta Harris, Fixed It XV1, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Melanie Roger Gallery.